A photograph can tell any given number of stories depending on the individual seeing it. A photograph may not have a story at all but will be precious for a person just because they have a memory attached to it. Now when you try to bring this use of photograph into a field like Architecture – Architectural Photography – where art, design, and calculations are technically balanced, this must have a pre-defined role and definition to be present there.

As a kid back in my 6th grade I had read a book on Photograph in my English literature class,(don’t remember the book name or author but) the theme of the book was to define the understanding of the story behind the photo when it was taken. Every photo will have two stories, one while it was being taken and another for what purpose it was taken. A small example on how the photoshoots of models go on, it is a work thing for the model but alongside that they are enjoying working and living their life while having the photoshoots.

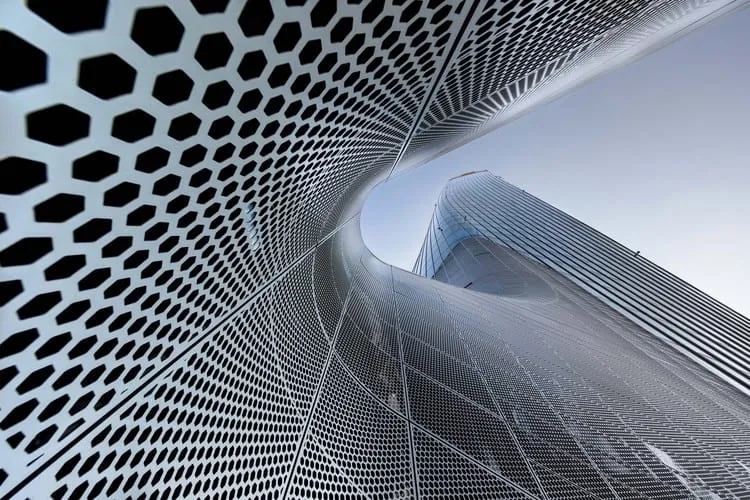

Now this same strategy if used in Architecture photography, will bring a broader definition to the photo itself while enhancing its visual language to the common public to not look at it just as a photo but also as an art display. But again, why have I used the first-word “Intersecting” in my heading? That is because many photographs must have been taken at the same structure or location, but is that going to be defining its language forever or the emotions too?

No, they were taken at the same location but by different individuals in different situations with varying emotions.

Architectural Photography – A Perspective

Architectural Photography – A Perspective

So, saying or justifying a definition to the photo forever will never work. It all depends on the moment and purpose. Now let us understand the subject more technically.

What is architectural photography?

Architectural photography is exactly what it sounds like; the photography of architectural structures. Great architectural photography needs to make the most of a structure’s design and environmental setting. The best architectural photography is interesting, aesthetically appealing, skillful and accurate.

Architectural photography should not turn to real estate photography

Real estate photography showcases properties with the intention of making a sale. Architectural photography, on the other hand, is focused on capturing the aesthetic and intention of a structure in the most interesting and unique way possible. You really must understand the Architect’s design intent to fully capture some amazing moments of the particular structure.

Basically, if you want to sell a house, hire a real estate photographer. But If you want to show off the distinct character and art of a structure, you need to hire an architecture photographer.

Architectural Photography

Real Estate Photography

Why you need an architecture photographer?

Architecture photographers can create images that are as bold and imaginative as the structures they are photographing. Architects put so much thought, time, and energy into their designs, so it is important that they hire a photographer who can do justice to their designs.

Everyone has a camera. Everyone knows how to point and click, and, yes, for selfies and fun memories these photos are simply fine, but for your business…probably not. In order to represent your business in a way that customers, clients and other professionals will respect and to get them interested in what you have to sell – it makes sense to use a professional architectural photographer to create high-quality, striking photographs that truly represent your brand.

No matter if you are an interior designer, architect, business owner or building materials supplier, you want your expertise highlighted. You want the colors of the room, the angles of the structure or the texture of your stones to impress your client. Awkward, dark, or boring photos will not do you or your product justice.

Every business needs to market itself. Whether used for print advertising, marketing brochures and materials, your website, or even just Facebook, your photos need to maintain the consistency of your brand. First, you want to maintain your brand personality. Is your company formal or more fun-loving? A professional photographer who specializes in your industry will stage the photos in the most appropriate way. Whether your photos involve products, people, buildings or food, a professional photographer knows the tricks of the trade to highlight the best features of your product.

Second, you want your actual photographs to look amazing. Poor quality photos can be a reflection of your business itself. People have an unconscious association: the photos are bad = the product is bad and/or the business does not even care enough to have good photos. So, even the best staging can be wasted if the lighting is not right or the angles do not capture the dimensions of the product while still having the emotions and artistic concept linked to it.

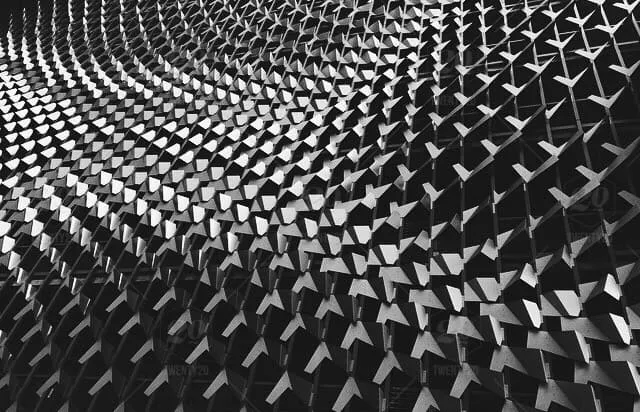

And speaking of lighting, professional lighting can truly make all the difference. Lighting can affect color, depth perception and more. We have all heard of celebrities demanding lighting to make them look better. Bright lighting can highlight certain features and deliberate shadows can hide flaws. This is true of architecture and design as well. Lighting happens to be my personal favorite – how light plays with space, both interior and exterior. The goal is to always maintain the integrity of the colors and lighting, as the architect and interior designer intended. It is important to evaluate the space at different times of the day to determine how the normal light (natural or otherwise) plays on the space. The final product must look completely natural as if you are standing right there. Capturing the natural shadows in these spaces should always be a great opportunity.

Additionally, a professional architecture photographer needs to be careful not to over-light an area. When you shoot a lounge area, for example, you should always maintain the drama of the shadows on the textured walls.

Post-production is an important component as well. A professional architecture photographer should be able to use a series of different techniques to correct any blemishes in the original shots while keeping them looking completely natural.

Good Photography is Important in Architectural Design

We are an image-obsessed society with extremely short attention spans. Images are registered and processed in the brain automatically. A photograph that contains people in some sort of setting not only tells their story but also showcases the subject and draws the viewer in allowing them to focus on the details. Architectural photography is no different, except the subject is most often a building. Photographing the space means a couple of things such as the job is complete, the building is whole, and the client is satisfied. Showcasing the client’s building is a privilege and should be treated as such. Take pride in creating the images. I suggest hiring a professional photographer that specializes in architectural photography.

Often though, a professional architecture photographer is not available due to schedules or budgets. As with any photography, insist on taking photos in the best light possible. Take photos at different times of the day. Shadows can create drama while sunsets create a warm inviting feel. Look for angles. Take photos from high angles and low angles; getting both perspectives allows you to create more interesting images.

Do not forget the details. Think of a wedding. There are so many details put into planning a wedding and you want to remember it all. You have photos of the cake, the rings, the flowers, the place cards and even the program. The same is true in photographing a finished building. There are hundreds of intricate details put into the design. Pay attention to lines and light and how they interact with one another. Lines draw the eye and can create an illusion of distance and depth. Look for textures of the interiors, the details of the railings and light fixtures. Take several images of the exterior as well as the interior.

Once you have your images, bring them into a photo editing software and finish telling the story.

Before and After Editing (above and below images)

Focusing again on the intersection of photography with Architecture

Architectural Photography is about a balanced transcription of a three‐dimensional world onto a small flat surface. It is also the testimony of the interaction between two closely related and yet somewhat distinct disciplines, whose interplay has grown entangled in recent times: while architects and historians continue to deploy photographs as indexical records of artifacts, buildings and sites are growingly identified with their photographic image as a consequence of the emphasis placed today on architecture as a form of mass communication.

The history of the partnership of architecture and photography is captivating for numerous reasons: it interrogates photography as an automatic drawing or a direct imprint of the constructed world, but it also accentuates the rhetoric and ideology of the photograph as an image crafted toward a particular communicative goal. From the start, when the invention of photography was publicly announced in 1839, a long series of enthusiastic observations by historians and photographers reported on the experience of physically “being there,” while holding a small daguerreotype of a Venetian palace or counting the detailed panes of glass of a window imprinted on a paper negative of one’s own home. These striking statements—articulated by John Ruskin (1819–1900), William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877), and numerous other travelers and historians of a time past—became layered with contemporary accounts that privileged the position of the architect as the main orchestrator of a message.

In his compelling study of Second Empire photographs by Édouard Baldus (1813–1889), Barry Bergdoll notes that “the photographer remained for the architect a nameless presence” and that “the photograph, or dessin photographique as it was often called, could be signed by the author of the building rather than by the author of the representation.” Furthermore, this seemingly transparent record responded to a precise agenda. Baldus’s photographic “style” carved buildings from the urban context with the specific intent of interpreting Baron Georges‐Eugène Haussmann’s (1809–1891) politics of dégagement, where monuments appeared as new beacons within open vistas. This attitude persisted for long since early twentieth‐century architectural historiography built its narratives on the identification between objects and their photographic representations.

In fact, if nineteenth‐century photography of architecture was characterized by an invisible and yet ongoing history of image manipulation and physical retouching, these considerations informed modernist practices even more radically. Beatriz Colomina and Jean‐Louis Cohen have profusely written on Le Corbusier’s (1887–1965) alterations of photographs in order to support his theories, and his profound understanding of the printed media as “a new context of production, existing in parallel with the construction site,” as exemplified by his early publications, in particular the journal L’Esprit nouveau.

Similar considerations about the symbolic use of photography apply to Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s (1886–1969) early photomontages, where the architect cut and pasted photographic reproductions and drawings of a projected glass skyscraper (1921–1922) and of the Adam Department Store (1928–1929) into the existing urban texture of Friedrichstrasse, Berlin, in order to build realistic—and yet unrealized—graphic projects. These alterations vary from perfect camouflages to Mies’s visible manual alterations, where the architect’s work—or signature—prevails over the mimetic qualities of the photograph. This symbiotic history of modern photography and architecture moves back and forth, from a critique of photography as a form of disconnect from the real (in particular, with Adolf Loos [1870–1933]) to its embrace as mechanical and industrial reproduction (with Walter Gropius [1883–1969] championing Bauhaus photography), to the challenge of translating the asymmetrical plans of Konstantin Mel’nikov’s (1890–1974) Constructivist architecture (in particular, his temporary pavilion at the Paris International Exhibition of Decorative Arts of 1925) into a well‐organized photographic description. Throughout the history of modernism, photography and architecture became intertwined in the publication and discussion of new projects, but the collaboration of these two media raised questions about representation and the actual experience of the building.

Such contested authorship, deeply ingrained in nineteenth‐century photographic commissions, has reached a complete turn with the postmodern debate, informing contemporary practices, and inducing architects to think increasingly “photographically.” As Benjamin Buchloh has observed, “advanced postmodern architects direct their design towards a new found ability of architectural masses, materials and spaces to yield to the laws of the photographic surface in an endless process of transforming the tectonic and spatial into the spectacular.” Similarly, contemporary photographers perform architectural practices, as in the case of German sculptor and photographer Thomas Demand (b. 1964) who transforms printed photographs retrieved from media into models constructed‐to‐be‐photographed.

It is evident from these brief notes and from the existing literature—mostly elaborated by historians of architecture and contemporary art theorists—that a debate on the relation between architecture and photography can only be produced through an interdisciplinary approach that takes into consideration the context of production and media distribution of images entailing two distinct—yet interconnected—authorships.

Architectural Photography – Between Documentation and Interpretation

In the post-postmodern era that we are living in right now, reality itself is neither clear as a concept, nor as a relevant parameter. When referring to ideals and perfection, people make conflicting comparisons. We often say that something artificial is so perfect that it almost seems real, whereas a nearly perfect experience is commonly described as almost unreal or dreamlike. Architecture is a discipline that works with both terms and reflects on the real and the illusive simultaneously. Therefore, both reality and simulacrum can be defined through various perspectives. We can talk about the reality of materials like the weakness of concrete or the solidity of glass. Analogously, architecture can be compared to the image of architecture. What is it, really, that an architecture photographer wants to accomplish, when displaying architecture? Are they trying to report on architecture and document its appearance, or trying to use the visuals to point out immaterial features? Is architecture used as a frame for events, and is it responsible for creating a certain atmosphere and provoking feelings?

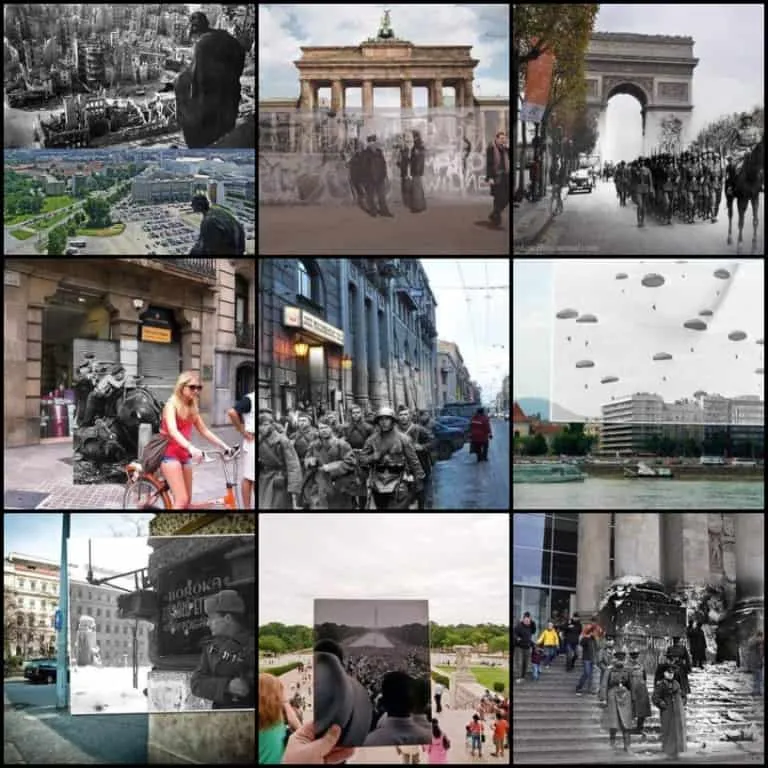

Architecture is not only about the building itself. Let us look at an obvious example: According to dailymail.co.uk, Guggenheim Museum in New York is the most photographed landmark in the world. The round-shaped spiral building, that looks nothing like the floor-wall-ceiling system we think of when imagining houses, has now become maybe even too familiar. The photographs expose it from so many angles (in and out, from above and from the ground), and as a result, people who have never visited the museum probably know what most of the building looks like. Guggenheim Museum has such a strong character, and yet it almost became a neutral space, something rather ordinary. The most interesting part is that, although photography mostly tends to preserve, in this case, it helped reveal the nature of a building of a certain age. Even more importantly, it demonstrated a simple fact that architecture is not resistant to decay. It does not have to become a physical ruin for its aura to become – well – old.

Architectural photography is more than just an offhand attempt to document a building, By the 1860s, architectural photography became an appreciated visual medium, and by the middle of the 20th century, architects started cooperating with photographers regularly. Buildings became highly valued subjects of photography, for one reason or another. They display cultural significance, and manifest trends in societies, which is an important matter of photography and its purpose of documentation. Leaders of totalitarian regimes used architecture to demonstrate power and dominance, from Fascist architecture in Italy, to buildings in the Soviet Union. These examples are only more recent, whereas the older ones – churches, temples, and castles, are even more obvious. And is there a better way to secure that these monuments remain permanent than to take photographs of them? Architecture photographers capture time and changes. They acknowledge the synthesis of the old and the new, the neoclassical and the modern, in a refined manner. They advocate architectural design and stage settings, but they also capture spontaneous moments that happen in and around buildings and landscapes and unveil their true character.

Architecture photographers use different techniques, and some of them are the same from the very beginning. To obtain a controlled perspective, they used to use view cameras, positioning the focal plane of the camera so that it is perpendicular to the ground. Today, photographers mostly use digital single-lens reflex cameras (DSLR), that provide different options when it comes to lenses, depth of field and controlling perspective.

Future of Architectural Photography

There is one more thing that evolved during the digital era, and its effect on architectural photography was inevitable. Experts deploy 3D programs for modeling and rendering to make images that perfectly illustrate the debate on whether reality is unreal, or whether the simulation is too real. Almost every architectural studio makes renders to visualize their projects before they are built, so that both the investors and the public can anticipate their future appearance. These images can vary, from obvious imitations to complete illusions, and photography seems to take a strange position when confronted with these techniques. It can be either used as a compliment, to work with the render and help provide illusive images that tend to simulate reality or as a concurrent stream that carries what renders can hardly ever provide – a touch of imperfection. My take on this argument technically will be that both are important and if in any case Renders do exceed the expectations of the photographs, then the photographs can be a part of the As-built stage of the project which will be visual documentation on what was proposed vs. what has been delivered.

** Mr. Biswajit Chakrabarty, a BIM Architect, based in Dubai has authored this article.